BY CARTER TRIANA

English is a growing necessity in South Korea. This is not only because of Seoul’s close relationship with Washington, D.C., but also because of the growing usage of English on a worldwide scale. Korean students who have mastered the language by the time they graduate from university have a much higher chance of employment than students who have not taken the effort to learn English. Korean parents are well aware of the importance of learning English and take measures to ensure that their children begin receiving English instruction at a young age.

The Korean hagwon is similar to tutoring programs in the United States. Parents pay to send their students to a hagwon so that they can receive extra instruction in a specific academic subject. Students typically go to their hagwon after school and spend several hours there. Although there are hagwons that specialize in nearly every subject, those that teach English tend to be very popular.

PAEDEA, the company at which we con- ducted our internship, has many branches located throughout the city of Seoul where students go to study. The branch that was nearest to the office where we worked was located in Seocho-gu, a district south of the Han River, which divides Seoul in two. During the workday, the time I did not spend in the office, I spent in the Seocho branch of PAEDEA. It took only five minutes to walk from the office to the building where the classrooms were located. After short elevator ride to the fourth floor of the building, I would walk through the reception area and into the teachers’ work- room. At first, all of the teachers seemed very surprised to see me, an American high school student, in the workroom, but after a couple of visits, they became accustomed to my coming and going. Eventually, I developed a relationship with the students and teacher from one class in particular and continued to return to the branch to observe that class.

The other striking thing about the students in this class was their handling of the English language. While they were only 10 years old and all learned Korean as their first language, they were so well-versed in English that they could already converse with others and understand the majority of television shows and movies they watched. I believe this is the best indicator of the willingness of the Korean people to learn and master the English language. Child- hood is the easiest time for one to learn a language and Korean parents have taken advantage of this––using Korea’s extensive hagwon system––to give their children a head start for the future.

Carter Triana is a senior at Pacific Ridge School. He is also a member of the Lingo Online service group at Pacific Ridge, through which he teaches English to international students via Skype. He hopes to study biology and pursue a career in the

medical field.

In mid-June we will be travelling to the capital city of Seoul, South Korea as part of our school’s global travel program. The purpose of our travel is to participate in a five-week long internship at a hogwon located in the Gangnam district of Seoul. Hogwons in Korea are comparable to tutoring companies in the United States. After their normal school day, almost all students will go to a hogwon that specializes in a subject in which they may need extra help.

During the workday, nine in the morning to five in the evening, we will be designing lessons and textbook material for use in the next semester of classes and observing teachers to determine the techniques they are using well in addition to the ways in which they can improve.

At the end of our trip, we will present the data we have gathered to the board of the company so that they can decide in what direction they would like to move the company.

Below is a sample of what a weekday may look like when we are in Korea:

7:45am - Wake up to get ready for the day.

8:30am - Breakfast on the run at Tom N Tom's Coffee

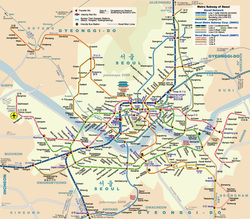

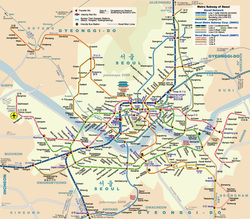

8:45am - Get on subway at Yeongdeungpo.

9:15am - Arrive at work in Seocho-dong.

9:20am - Morning meeting with Research and Development staff.

10:00am-12pm - Work on textbook materials for Fall 2013 semester.

12pm-1pm - Out for lunch, bibimbap

1pm-3pm - Go to Apgujeong branch to observe classes and gather data.

3pm-5pm - Read relevant research and work on presentation.

5pm-9pm - Eat dinner and explore the city.

The man of the hour, Kim Jong Un

The media in the United States tends to blow things out of proportion, especially when international issues arise. The recent news about military movement in the Korean Peninsula as well as the “threat” of a nuclear strike on the United States has found its way to the top of American tabloids. Many Americans have begun to express their fear of the situation because of the extraneous nature of stories in newspapers and online.

South Koreans, however, have a different opinion on the subject. Most South Koreans have developed a sort of immunity to the threats from North Korea. The woman who owns the guesthouse in which we will be staying for half of our trip explains that these threats come about once every ten years. With major developments of information access in the 21st century, the issues are now at the forefront of America’s attention instead of common occurrences, as they are seen in the eyes of South Koreans.

Being exposed to American media on a daily basis, whether from the news or online, we have to admit that we were very nervous about the current situation on the Peninsula; however, after speaking with Mr. Strong, our guesthouse contact, and students that I have tutored in the past, our opinion on the matter has changed considerably. Although much tension is present and we cannot just ignore the possibility of danger, we have become much more relaxed about the situation and the capabilities of the global community to respond to the potential threats posed by the North Korean government.

-CJ

What defines someone as facially attractive? Is there a set equation for which features amount to beauty? Well, yes—and no. No, because many people have specific preferences that may not be considered conventionally pretty, and often men and women with unique, and sometimes disproportional, features are thought to be ethereally beautiful. But while not everyone has an affinity for unusual faces, even those who find bizarre looks enticing cannot deny that say, Jennifer Lopez—named the most beautiful person of 2011, is good-looking. There are certain characteristics that are universally attractive: proportional face, large eyes, clear skin, defined bone structure, full lips, etc. What I’m getting at will become clear later on, but keep these beauty standards in mind as you continue reading.

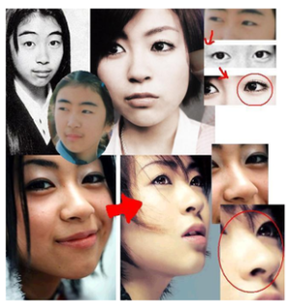

As discussed in my previous post, plastic surgery in Korea is, well, not that big of a deal. Of course, it’s a huge industry; invasive plastic surgery is so prevalent in Korea, that an estimated 15-30% of all women in Korea, young and old, have had plastic surgery, and that number skyrockets when looking at the statistics for women under 30.

But the nonchalance of Koreans towards the alteration of facial structure is surprising, to say the least. Preteen girls, barely starting to develop their adult features, are getting nose jobs and eyelid surgeries. What would cause uproar in the US, leading to news stories about child abuse and poor parenting, are the happenings of a typical weekday in Korea. But why? Why are so many Korean women unsatisfied with their natural beauty? And exactly what are they striving to look like anyway?

Well, that's where things get tricky.

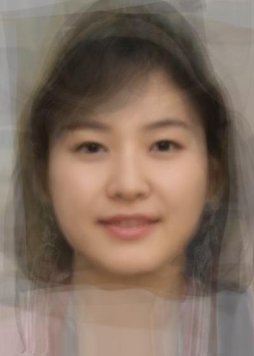

The photo on the left is a composite of over 100 random Korean women from Seoul, while the other is an averaged face of female idols, women who are considered the most attractive in Korea. Spot the differences? The most obvious between the two faces is age, the first looking slightly older and more matronly, while the idol face appears to be in it's teens or early twenties. Like Western societies, East-Asian aesthetics revolve around youth. Korea and Japan in particular seem to have an undeniable obsession with having a youthful, yet sexy, look. Korean netizens (Net citizens aka internet/forum frequenters) have even coined a neologism, ba-gl, or bagel, stemming from baby-face and glamorous. So called “bagel girls”, are the current epitome of beauty, and usage of the word has erupted into mainstream Korean media from such online argot.

Another difference between the two images is the actual shape of face. The average Korean woman’s has a broader jaw, and a seemingly wider structure, while the idol’s is slim and petite, with a v-shaped jaw. Both of these aspects reflect the ideals Korea holds for the very bone structure of it's women. Generally, due to facial flatness, and an overall wider facial bone structure, Korean faces tend to appear larger than the typical Westerner. I say appear because this has been proven to be false, yet the stigma remains, and as a result, many Koreans, both men and women, are self-conscious about the size of their faces.

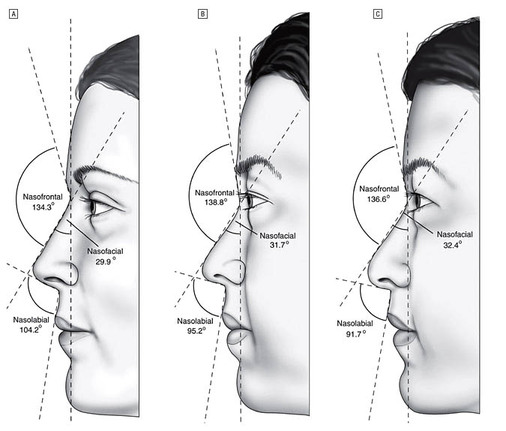

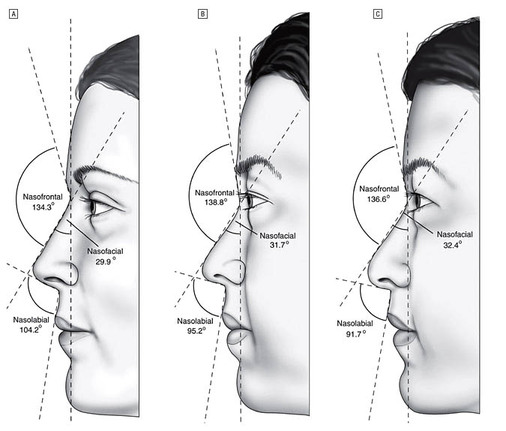

The average female profile dimensions of: (from left to right) North-American, "ideal" Korean, and Korean women.

For this reason, a common comment on popular Korean celebrity gossip sites references the "smaller" faces of idols. Another popular comment references the presence of a “v-line”, in both male and female idol faces. As discussed in my previous post, a v-line is the v-shaped, narrower chin that many models and celebrities possess. The media has latched on to this buzzword, and a wave of products, ranging from drinks to face rollers, which claim to create a more defined v-line has washed over the advertisement industry. As expected most of these items are...less than effective. Luckily, there is an alternative....plastic surgery.

This will surely work! So, can you guess what the most popular plastic surgeries in Korea are? Well, to start, procedures unique to East Asia such as the jaw-line reduction are very popular. For those of us born with a wider jaw, even the most relentless face rolling won’t slim our large chins. But never fear, because for only a few thousand dollars, our jaws can be slightly streamlined by way of Botox, or, for people who can afford it, surgically shaved down to a point. Yippee. Don’t get me wrong, I have nothing at all against plastic surgery, I liken it to any other body modification, albeit more drastic of course, so jaw-line reduction offends me in no way other than the fact that I have now realized I have a big fat chin. Other surgeries include calf-reduction and cheekbone shaving, and, converse to typical Western nose jobs that reduce the nose, augmentation rhinoplasty (the building up of the nose’s structure).

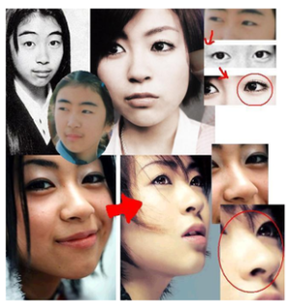

The by-far most popular cosmetic operation in Korea, as well as the rest of Asia, is the eyelid surgery. The procedure is meant to make the eyes appear slightly larger by making a slight incision in the eyelid and folding up part of the fat so that a double eyelid is formed. To make this slightly less confusing, here is a comparison between a single eyelid, found on most mongoloids, and a double eyelid, found on most Caucasians. As you can see the monolid can often conceal part of the eye, making it appear smaller, or squinter, than an eye with a double eyelid, which appears more open and deep-set.

Top: monolid; bottom: double lid (after cosmetic surgery)

And as one might expect, procedures such as breast augmentation, liposuction, and facelifts are also common in Korea, as well as the rest of the world. But the aforementioned alterations—cheeks, jaw, calves, nose, eyes—are almost nonexistent outside of Asian countries and communities.

Now, the controversy surrounding the high rate of plastic surgery in East-Asian countries, mainly relies on defining what, exactly, the standard for beauty is. It may seem that, given these countries most popular surgeries, Asian women are wanting to look…. white. They want larger eyes, less prominent cheekbones, pointier noses and jaws, and pale white skin (I’ll get to that in a separate post) all typically Caucasian features. The media in many countries has latched onto this idea, and frankly, it’s gotten out of control. While many Caucasian girls, including myself, may feel ecstatic seeing these assumptions, (I mean, if every other race of women wants to be white, then how lucky are we!) in my opinion, they are--understandably--wrong. Mainly because there are some beauty standards that may seem "white" but are really universal, developing independently in their respective corners of the world. It is true that American and European media and culture has been infiltrating other countries at a rapidly increasing pace over the past few decades.

I think one of the most interesting examples is the love of white skin in East Asia. I have seen countless blog posts and heard directly from some of my Asian friends that their mothers insist they stay out of the sun, and sometimes even give them products that lighten skin tone. Now the phrase “milky white skin” is thought of as the ideal for these women, suggesting that they have a desire to be white. But, on the contrary, pale skin has been a sought-after feature long before East Asia made contact with Westerners. Look at images of Japanese Geishas—their faces painted to a pure white—and they are the ultimate models of beauty, appearing even before the first Caucasians arrived in Japan in the 17th century.

The reason why white skin was preferred was the same as why Europeans also prized pale beauty: the rich didn’t need to work outside; therefore their skin would stay pale. On the other hand, the common laborer would have darker skin from staying out in the sun all day, signifying their poor status. Unfortunately, while this explanation may justify why white skin is so desired, it also serves as a basis for discrimination against darker skinned persons, especially in Korean, a topic that will be fleshed out in a skin focused post. (Hehe, fleshed out? Get it? Get it?)

And for one final tidbit to chew on, consider the ideal skin tone here in America. Ahhh, that’s right: tan, olive, sun-kissed, bronzed, etc. What a strange juxtaposition! I think many a Korean would be perplexed to discover that Westerners spend countless hours in the sun—on purpose, and would even be horrified to find that we have unnatural methods of imitating the rays of the sun, from spray tans, to bronzing makeup, and the ever infamous tanning bed.

Back to the topic of surgery, many of the more “Asian” procedures, actually have Western counterparts: nose augmentation in the East, nose reduction in the West. Cheekbone reduction to cheekbone addition. Eyelid folding to eyelid smoothing. So why do we assume that Asian women want to look white, instead of the other way around? And with our excessive tanning, why isn't it assumed we desire to be African or Latin?

In short, there are certain features that are just aesthetically pleasing, no matter what ethnicity you happen to be. Large eyes are generally associated with youth, so it's no surprise that in cultures that value youthful beauty, makeup and procedures that claim to create larger eyes are popular. On the other hand noses usually aren't considered better or worse depending on size, but large, crooked or bumpy noses are seen as more masculine, while delicate, slender ones are considered feminine. And on the other other hand, regarding things like skin tone, hair color, and other uncategorized features, the motives pushing women and men to change said features are numerous, be it for exoticness, shock value, aesthetic preference, and more.

Although I agree with the claims that Western influence has played a large part in the plastic surgery industry, I can't bring myself to believe that all Asian women that receive cosmetic surgery are consciously desiring to be white. (Though, since I am not Asian, and I grew up in a Western country, I admit that I probably don't have the necessary insight when discussing these issues. Much of this information comes from two college-age Korean women that I have talked with about the social pressures and nuances of plastic surgery in their country, as well as idle chat with Asian-American friends and hours of online research.)

Keep in mind that this is all just my opinion, and there are numerous theories out there regarding the source of the "flawed body" mindset that many Asian women hold, so please, leave your comments and opinions below!

-Emily

Excuse my rather long commentary. This is a post informing you of the rise of plastic surgery in Korea that took an unexpected turn somewhere in between "discussing Korean culture" and "criticizing American ideals," bypassing all facts and information that this message was supposed to contain. Yet I thought it was still worth posting. Enjoy my ramblings.Last year, I came across this short, 20-minute interview-style documentary about life at a Korean high school. Wow. I learned more about self-image in twenty minutes than I have in years of sitting through health class. I thought I knew how crazy the world of beauty and perception could get; having friends that are models and, well, just being a girl in a society that values appearance gave me pretty good credentials-- I thought. Was I prepared for all of the "I'm not beautiful"'s? Or the "Beauty means boyfriend"'s? No. The first time I saw this film I cried. Out of shock, out of sadness, out of wanting to tell these girls that they were beautiful, that they were worth more. But that, my dear readers, was when I was naïve to much of the Korean culture. Now I know that "you need a diet" and "you need plastic surgery" are perfectly fine things to say to your peers. Not rude at all.These girls in the documentary were explaining what they wanted needed to be accepted: wide eyes, double eyelids, light skin, and long and skinny legs. This is CRAZY, I thought. It's not reasonable. Based on these criteria no Korean could be born beautiful; it just isn't genetically possible. There's nothing more depressing than having a non-achievable standard of beauty—or of anything else really, but I am coming to the conclusion that the exact point of Korean standards is to be unachievable.

SNSD girl group- teen stars set beauty standards. "If there's a will, there's a way"—and that way is plastic surgery. I've never considered plastic surgery. I mean why would I? I'd say that's not at the top of most American girls' wish lists. Actually, it's probably not anywhere on their wish lists…(with the scattered exceptions of the "plastics"--high society girls I see stereotyped in movies. I'm sure they exist somewhere like New York or L.A., but I've never met one). Plastic surgery isn't on most Korean girls' wish lists either—it's on their to-do lists!

"I have to do it; beauty is important in Korea," replied a student after being told she didn't need plastic surgery. "Before, I was ugly, but now I've become pretty," another girl commented on her recent change. (My heart is breaking for them.) According to JoonAng Daily, 41% of Korean teens are willing to undergo plastic surgery to become "beautiful."

There are stark differences in culture and mindset that cause me to react to this:

~Stigmas~We Americans like the "all natural" approach. We tend to hold others in disdain if they get cosmetic surgery, cake on the makeup, or get any advantage over the rest of us that was not by their own hard work or natural luck. Not that we aren't hypocrites—we are. Why do we have "natural look makeup"? Isn't that just an oxymoron in itself? Does that set a new standard of "natural beauty"? If so, it's now naturally unattainable, just as the Korean standard is.

Americans are bought by "pure" and "natural." But why do we worship a celebrity's beauty, then scowl and slander when we find out she's had breast implants or a nose job? Doesn't beauty equal popularity? Are we jealous? Do we do this to flaunt our own beauty; to discredit the opponent? Any given American, after getting plastic surgery, will hide. She is ashamed of it. Maybe she will alter her nose a little at a time, start at a lower concentration of Botox, and work up her injections gradually, because she doesn't want anyone to notice. Does that make sense?! I don't know.

Koreans are more open about plastic surgery. While American celebrities get treatment in secret, Korean stars flaunt it. They are inspirations. I do not understand this huge difference between our cultures.

Americans believe in fairy tales and fantasies. We fall into this way of thinking that beauty is given to the lucky, and the lucky live lives that we should adore. Does this confession of falsity and unnatural beauty shatter our rose-colored vision? Are we angry? Angry at our own gullibility? We find ourselves back at the gut-sinking feeling of disappointment, of melancholy, as we did when we were 11 and didn't get our acceptance letter to Hogwarts via owl—because Hogwarts no longer existed. The same empty feeling as when we were playing house, and we were no longer able to conjure up that imaginary stove to make the imaginary dinner—because it no longer existed. The concept of "natural beauty" no longer gave us hope, no longer gave us comfort or joy—it no longer exists. Not according to our ideals of beauty. But to say so is taboo.

Korean teens are prideful about their surgeries. The "stick-out-nose" and the "double-eyelid" become the envy of their classmates. There are no qualms about ditching the concept of natural beauty. "Sang Ka Pul (double eyelid) glue" offers daily help for those trying to attain the "western eye look." The girls aren't ashamed of it; they pass it around as my friends would pass around a miracle-working mascara. "This one is pretty," a girl says as she points to her "fixed" eyelid. This method seems to obviously painful and unnatural, but we can't criticize while we twist our ankles in high heels, and exfoliate entire layers of skin off of our faces.

Proud student showing off her Sang Ka Pul glue. ~Seeking affirmation~We give positive feedback to friends. "You look great!" "You're so skinny!" We say these things to our friends especiallywhen they're at their lowest. We are a nation of e-tank boosters. Yipee.

"You should go on a diet." "You're ugly." "You need surgery." These comments are more commonly heard in Korean schools. Again, this is NOT considered rude in Korean culture. They aren't being mean; they're saying what they perceive. Watch the documentary and weep when the girl says that the first time her mother told her she was beautiful was after she got plastic surgery. My friend living in Korea affirmed this for me: many parents push their children to get plastic surgery. They believe success is linked to beauty, which, let's face it… has become the truth.

Now, personal anecdote of the week:I don't wear makeup. I wasn't allowed to in middle school, and never bothered to learn the basics of wearing makeup once I entered high school. Honestly, I don't have time to spend on my appearance. I'd rather get the extra half hour of sleep. Save the stress for a better cause. My friends, on the other hand, care a lot about their appearances. They find fun in choosing which color of eye shadow matches their uniform, or deciding whether to straighten or curl their hair each morning. Now, my mom gave me eyeliner and mascara last weekend. I wasn't super interested, but I wanted to do a little experiment. I wore (hardly any) makeup to school on the morning of January 26th. The first classmate I saw told me, "Katie, you actually look pretty today." Why thank you, kind classmate. Good to know I don't usually look pretty, but thanks for the backhanded compliment anyway. Many like-minded comments flowed my way the whole day. I noticed people talked to me more that day. They walked with me where I usually walk alone. No make up the next day. No compliments. I wondered if that's how it felt in Korea after getting plastic surgery—having friends, having power.

Pretty isn't enough...but beauty is power?

It made me think about the relationship between beauty and success—not in America, not in Korea. Humans are shallow. We like things that shine. We like pretty people. When given a choice, don't we always choose whatever it is that we like? Yes. Seeing this trend, how could one who wants to succeed not gravitate towards conforming to their audience's standards of beauty? To succeed one must play to the judges, no?

I don't believe that beauty should be the basis of success, but does it look like I make the rules of society?

No I don't. But I contribute to their enforcement and so do you, on accident, on purpose.

I would love to get into the psychological effects and complexes due to the standards of beauty imposed upon teenage girls, and the debate of "does self-image = confidence?" but I think I've gone off-topic enough for one post =) Hope it made you think! ~KD

This article, written by Katie Dillon, Maggy Ryan, and Emily St. Marie, was published in the Global Vantage in the spring of 2011.

I have always been a typical girl. Not an average human being that happens to be of the female gender—a typical girl. Toy trucks never amused me, nor did football, fast cars, or the color blue. Tea parties and Barbies entertained me for most of my childhood, as they did for most of my friends. Except for one girl: my sister.

When I was little, about four or five, my little sister—who is two years my junior—and I would spend countless hours playing “house.” Well, not really house, more like dress up in our favorite costumes and run around looking for attention from the rest of the family. Almost every time we played, she dressed up in overalls and a hard hat as a construction worker, while I wore sequins and boas like a model. Of course, she was younger than I was, and, like many children that age, she didn’t know that it was unusual for a girl to want to be a manly construction worker.

Many children of young age are often androgynous, if only for a few years. This androgyny stems from innocence and ignorance. Young children have no sense of how a girl should act or dress; they have no idea that boys are supposed to be tough and never cry. Only once we reach a certain point of understanding do we start to define ourselves as either feminine or masculine in society’s view. Yet, as we grow older, some of us choose to cross or blur the line between male and female and their attached stereotypes. For example, going back to my sister and me, although I used to adore all things girly and she used to be a spunky tomboy, our roles have reversed as we have grown older. Now, I am the one shopping in the men’s section, and she has finally begun to accept that pink is a pretty decent color.

Luckily, in America, people are generally accepting of the idea that gender is fluid and is not black and white—or should I say blue and pink? It is not unusual to see women in the military, and it is quite common for men to become teachers and stylists, professions that were previously considered feminine. The United States is an open-minded nation, and while individuals and groups here and there still follow strict rules regarding gender roles, the United States as a whole is tolerant and progressive when it comes to feminism, sexuality, and gender.

Many people hold the opinion that the West is years ahead of Asian cultures in women’s rights—and they might be right. To illustrate this, my fellow students and I will compare American society with South Korean society.

We students at Pacific Ridge School live in a country and era where women are as free as men, so we interviewed our Korean students to get a real-life perspective of women in South Korea. My schoolmates and I have built relationships with women studying at Ewha Womans University in Seoul through our service- learning group, LingoOnline, and we teach them English once a week via Skype. Our students love not only learning about American culture, but also sharing Korean culture with us. Through this cultural exchange, we have discovered that gender equality is not a universal concept, and we are determined to figure out why. Through both research and interviews, we have concluded that Korean history, religion, culture, and media all play parts in restricting the advancement of women’s rights.

The roots of South Korea’s discrimination against women stem from ancient Korean culture. The indigenous religion of the people was Shamanism until China introduced Buddhism to Korea in 372 AD. Buddhism is a belief that one is born into a cycle of suffering: birth, life and death, and rebirth. This cycle continues until one reaches Nirvana, the state of enlightenment. A woman can reach Nirvana, but she cannot attain the title of a Buddha, a Brahma king, or other high spiritual accreditation. During Buddha's lifetime in India, an order for women, the Bhikkhunis, was established shortly after the order for men, the Bhikkhus. While this is seemingly “equal,” there were eight rules placed upon the Bhikkhunis that gave the Bhikkhus the irreversible power to preside over the proceedings and status of the Bhikkhunis. The order of the women had entered a decline after Buddha’s death and is no longer in practice, whereas the Bikkhu order still exists today.

Although these orders did not originate in Korea, the ancient mindset of gender discrimination came along with the religion. This mindset is unrelenting even through changes in the religion itself. When Confucianism came to Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty in the 1300s, followed shortly after by the Joseon Dynasty, higher education centers were established upon Confucian curriculum, and both the social use of Confucian ideals and a patriarchal family system were encouraged.

Confucianism is based on the belief that every man should know his given place. A ruler is a ruler and should be treated as such; a subject is a subject and should be subordinate to the ruler. A father is a father, and he is to be treated as a father, respected and holding authority, yet he is subservient to the ruler. The idea that a woman’s place is in the home to keep house, cook, bear sons, and answer to the men stems from Confucianism, and this idea is still the norm in Korean society today.

While women are certainly not yet considered equal to men in Korean society, stereotypes are diminishing and rights are increasing. The national constitution prohibits any act of discrimination based on sex and declares female and male to be equal individuals. In 1948, women won the right to vote. The Equal Employment Opportunity Act passed in 1987. In 1989, the Family Law was revised to state that all family inheritance must be distributed equally among daughters and sons, as opposed to the tradition of having the first son inherit all family possessions and real estate. The Basic Women’s Development Act of 1995 was passed to encourage women’s participation in economical, political, social, and cultural fields. The Labour Standards Act, passed by the Korean Ministry of Labour, provides safer working conditions for women and minors, as well as prohibits them from being employed for any work that would be “detrimental to morality or health,” working for more than two hours overtime each day and during dark hours and holidays. The Special Act for the Punishment of Domestic Violence came into effect on July 1, 1998 and allows women to seek protection from spousal abuse.

All of these laws have changed the legal standing of women for the better but have not eliminated the social and cultural stigmas against women.

Despite all the laws protecting women and their rights, women in Korea still do not enjoy the same opportunities as men. My student Jinsun, with whom I have made contact through my service-learning group LingoOnline, explained that even with equal employment laws, it is still hard for women to find work. In many cases the equal employment laws work against women. This is because employers must by law give a pregnant woman thirty days paid leave both before and after giving birth. Pregnant women must also be given easier workloads while still receiving their regular pay, resulting in companies trying to avoid hiring women. “After you give birth to the baby and get maternity leave, you can’t go back,” Jinsun said. “The companies don’t like those women, so it’s really hard to raise kids in Korea. Many young couples just give up raising kids and live together without starting a family.”

Jinsun believes that Korea’s discrimination against women is both discomforting to and limiting for them. She explained her observations of male supremacy: “In Korea, men usually try to deal with everything. When [my boyfriend and I] dated, he always carried my bag; it’s common in Korea nowadays. Among many young couples, the man carries the girlfriend’s bag. I think the men have some philosophy that they should protect their girlfriend and provide every comfort. It’s a very passive attitude. I want it to change, because when people are dating, it’s okay. However, when they get married, the women are still very passive and they obey the men’s order or men’s decision. Nowadays it’s better; but still, many women follow the decisions made by the man and endure his decisions.”

To better understand this lifestyle, we envisioned Jinsun’s situation in America. In America, we do have the same stereotype that men must be bold and brave, and that they must protect women. However, we realize that there is much more freedom in the realm of relationships in America. Although we do have such stereotypes, it is not uncommon to see confident women approach less assertive men in a relationship.

Another influence on Korean culture is advertisements aimed at each gender. We found the following ads to be particularly effective at establishing the difference between the two genders.

As you can tell from the pictures, there are obvious stereotypes regarding gender in advertisements in Korean culture. For example, in this ad for children’s accessories, the separate pictures for the boy’s line and the girl’s line demonstrate the general ideas behind how women are perceived in Korea. The glaring difference between the opposing color schemes is a common advertising technique to visually split femininity and masculinity.

While these highly visible traits make the distinction obvious, other ways these pictures divide gender are more subtle. First, the environment the children are placed in makes a bold statement. The girl is in her closet, surrounded by clothes, bows, and frills. Her posture is slightly bent to the side, in a cute, submissive way. The picture is very cramped, creating a slightly claustrophobic feeling. What is the little girl doing in her closet? It appears that she is thinking about what she is going to wear that day—so many cute things to choose from!

Now, how about the boy’s ad? In this photo, ships and planets surround him. He is clothed in futuristic clothing and gear. The deep realm of space stretches into infinity before him, and the boy has a strong, powerful stance, his back facing the camera. It seems as though he is pondering where to explore. Compared to the young boy’s thoughts, the girl’s seem petty and trivial.

We must ask ourselves: Is this what men think women dream of? Shoes and purses? Can only men be adventurers, scientists, and astronauts? While advertisements may not seem like a driving force behind gender inequality, the media does play a huge role, for better or for worse.

These two examples of Korean advertisement, along with countless others, were found in the English blog “The Grand Narrative,” which focuses on Korean sociology through gender, media, and popular culture. Written by James Turnbull, who currently resides in Korea, the blog has discussed South Korean feminism multiple times, stating that a lot of advertising, along with other aspects of Korean culture, is still discriminatory against females.

For example, a 2010 survey taken by 1,623 Korean women showed that 71.4 percent believed that promotional systems at their jobs placed women at a disadvantage. Luckily for Korean women, this situation is beginning to change, and the voice of feminism in South Korea is a larger driving force in politics, media, and everyday life than it was only fifty years ago—women are gaining political representation and beginning to experience equality in a persistent patriarchal culture.

The changes that have been taking place over these last years are not progressing as quickly as the changes in other countries, such as the United States, but they are progressing nonetheless. It is not often that one hears about feminism and women’s rights in other countries because it has become the norm for women in America to be equal in almost every field. We tend to dismiss news of small victories for women as old news.

What we do not realize is that not all women have the privileges that women in America do. Deeply rooted culture, religion, and philosophy in Korea have caused the scales to tip in favor of men. While progress has been made, sexism is still present in both the media and the minds of citizens, as shown by the opinions of our students. Education, work, and general discrimination against women, unfortunately, is still alive in South Korea, as is the ridiculing of both female and male feminists. Feminist author Joohyun Cho explains in her book Gender Identity Politics that early Korean feminists were not taken seriously, and that even in modern times feminists are sometimes shamed for their views. Luckily, this discrimination mainly occurs among the older generations and is not how the majority of young adults feel about equality. Jinsun gave us a first-hand account of this idea and showed us that young women are concerned for their futures in a male dominated society, but are hopeful about progress that can be made over the next few years.

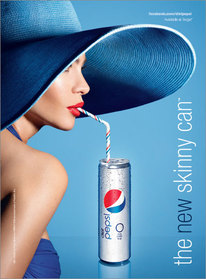

How refreshing. When watching television or browsing online, one can hardly go a few minutes without being bombarded with advertisements hailing the newest weight-loss program or “lite” energy drink. Not surprisingly, these advertisements reflect the persistent influence of the media on female body image.

As a girl, I am no stranger to the brashness of the media when it comes to dictating how I should look. The most frustrating part of this section of our culture, is the unrealistic appearances of professional models and actresses, each with their own team of stylists, whose only job is to make them look beautiful. Now, I have nothing against the way these women look, only with the pressure they put on women to look and act the way they do. Although, in comparison, I would have to admit, that from an outsider’s view, Korean women (and men) are held to even higher expectations when it comes to their bodies. I am actually quite thankful for the diversity of American stars and celebrities, as compared to idols in Korea.

For example in the United States, although most fashion models are tall and thin, many of the women who are considered to be some of the most beautiful in the world are “curvy”—Kim Kardashian, Christina Hendricks, etc. There is also a wide range of hair cut and colour, height, and—very importantly— skin tone.

In Korea, and other East-Asian countries like China and Japan, this range is restricted to only a few types of women. Few female Korean celebrities weigh over 55 kg, and if they do happen to have a little extra weight, the risk of being labeled “fat” is almost guaranteed. In fact, a Korean pop girl-group even attempted to change this set negativity surrounding bigger bodies. Park Ji Eun, one of the girls in the group, called the Piggy Dolls, said in an interview, “When we first auditioned, there were three conditions. First, we had to be talented vocally. We also could not have had any plastic surgery done, and we had to weigh over 70kg.” Unfortunately for the Dolls, their initial popularity was pretty low, even for a newly formed group. Though no one can say for sure if they just lacked talent, or if their image was not mainstream enough, here’s the real kicker: after they failed to receive much attention, all three of them “coincidentally” lost almost 20kg each. And now let’s compare, on the right, currently one of the most famous singer’s in Korea, Lee Hyori, often praised for her slender figure. On the left, the new and “improved” Piggy Dolls.

S is for sexy. Strangely enough, while most idols tend to be on the very thin side of the scale, the hot new body type in Korea involves “curves”. Now, when I say “curves”, I don’t mean the curves of the woman in the center of the Piggy Dolls photo, and definitely not "American-style" curves a la Miss. Hendricks—I mean seriously, she would be a whale by Korean standards. The curves I'm referring to are so subtle that during my research (aka oogling photos of Korean celebrities for a few hours) my untrained eye couldn't distinguish an average figure from the elusive curvy one. Honestly, most of the women’s bodies appeared very slight in frame and slender in weight; the only curves I could make out were in photos where the girl was intentionally arching her back and jutting out her chest, as shown to the left.

This brings us to another phenomenon unique to Korean popular culture, body lines. Featured above is the “s-line”, or the s-shape made when following the form of a woman’s backside to her chest. Other notable “lines” include the x-line (chest, waist, hips), m-line (abs, used for men), and the ever-popular v-line (a narrow, pointed chin, and sometimes used for the “v” between breasts). Since there are over 20 different lines to describe the male and female forms, there will most likely be a whole 'nother post dedicated to the craze, and the advertising that has evolved along side it.

There are literally dozens of facets related to beauty standards in both Korea and America, and since I hope to do justice to each one, I won't waste time trying to skim over each topic. So stay tuned for upcoming posts on:

-The desire to be tan in America vs the desire to be fair in Asia

-Facial beauty-Is caucasian the ideal?

-Korean body lines in advertising

and the controversial....

-plastic surgery

| |

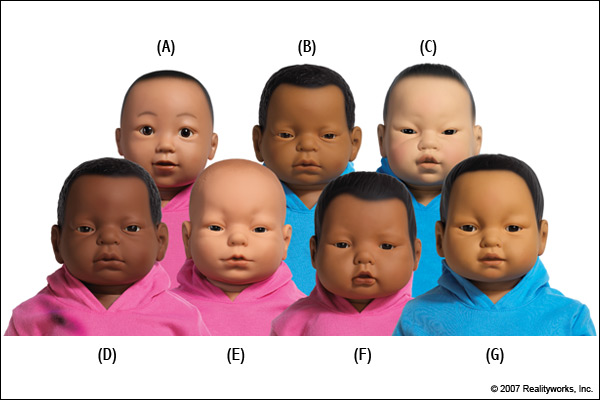

Babies guarantee a successful blog.

|

See you next week for a dissection of the rest of the human body! (Not literally. Well maybe just a smidgen.)

-es

Welcome to Got Seoul, our blog dedicated to South Korean and American cultures, linguistics, and influences.

We, Emily and Katie, began our intercultural exchange when we became founding members of the LingoOnline service-learning group. We found ourselves talking to Koreans weekly, immersing ourselves in their lives through language and culture. Later that year, we were asked to write an op-ed piece on Korean gender roles for the Global Journal Project, which was published internationally. Under that venture, our love for the Korean lifestyle and writing evolved into the desire to share, absorb, and understand a variety of cultures.

We don't know exactly where this blog will take us, but we are heading down the path of discussing South Korea's current events: from education, language, and work life to feminism, materialism, and pop culture.

Contact us if you would like us to cover a certain topic or issue!

Start blogging by creating a new post. You can edit or delete me by clicking under the comments. You can also customize your sidebar by dragging in elements from the top bar.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed